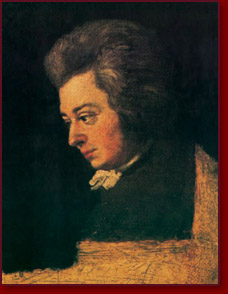

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 – 1791)

Wolfgang Amdeus Mozart was born on 27th January 1756 in Salzburg, as the son of Leopold Mozart, court violinist and deputy Kapellmeister of the cout orchestra.

The father wisely guided the child-prodigy “Wolferl” in a conscientious, all-round education. Concert tours took the young Mozart all over Europe. The father knew when the time had come to encourage his sons’s Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart became on of the most versatile musical geniuses, creating unforgettable works in all styles of composition. The Köchelverzeichnis, which lists all Mozart’s works, includes 626 compositions in the most varying musical styles. Among them are church and secular music, as well as vocal and instrumental works.

No other 18th century master has left behind music which is still so fresh and lively, and as effective on today’s stage as the works of this great and most famous Austrian.

Child of prodigy (1756 – 1771)

Family and early years

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born to Leopold and Anna Maria Pertl Mozart at 9 Getreidegasse in Salzburg, capital of the sovereign Archbishopric of Salzburg, in what is now Austria. Then it was part of the Holy Roman Empire. His only sibling to survive past birth was Maria Anna (1751 – 1829), called “Nannerl”. Wolfgang was baptized the day after his birth at St. Rupert’s Cathedral.

The baptismal record gives his name in Latinized form as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart. He generally called himself “Wolfgang Amadé Mozart” as an adult, but there were many variants.

His father Leopold (1719 – 1787) was deputy Kapellmeister to the court orchestra of the Archbishop of Salzburg, and a minor composer. He was also an experienced teacher. In the year of Mozart’s birth, his father published a violin textbook, “Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule”, which achieved some success.

When Nannerl was seven she began keyboard lessons with her father, and her three-year-old brother would look on, evidently fascinated.

Biographer Maynard Solomon notes that while Leopold was a devoted teacher to his children, there is evidence that Wolfgang was keen to make progress beyond what he was being taught. His first ink-spattered composition and his precocious efforts with the violin were on his own initiative, and came as a great surprise to Leopold. Father and son were so close that these childhood accomplishments brought tears to Leopold’s eyes.

Leopold eventually gave up composing when his son’s outstanding musical talents became evident. He was Wolfgang’s only teacher in his earliest years, and taught his children languages and academic subjects as well as music.

1762 – 1773: Years of travel

During Mozart’s formative years, his family made several European journeys in which he and Nannerl performed as child prodigies. These began with an exhibition in 1762 at the court of the Prince-elector Maximilian III of Bavaria in Munich, then in the same year at the Imperial Court in Vienna and Prague. A long concert tour spanning three and a half years followed, taking the family to the courts of Munich, Mannheim, Paris, London, The Hague, again to Paris, and back home via Zürich, Donaueschingen, and Munich. During this trip Mozart met a great number of musicians and acquainted himself with the works of other composers. A particularly important influence was Johann Christian Bach, whom Mozart visited in London in 1764 and 1765. The family again went to Vienna in late 1767 and remained there until December 1768.

These trips were often arduous. Travel conditions were primitive, the family had to wait patiently for invitations and reimbursement from the nobility, and they endured long, near-fatal illnesses far from home: first Leopold (London, summer 1764) then both children (The Hague, autumn 1765).

After one year in Salzburg, father and son set off for Italy, leaving Wolfgang’s mother and sister at home. This travel lasted from December 1769 to March 1771. As with earlier journeys, Leopold wanted to display his son’s abilities as a performer and as a rapidly maturing composer. Wolgang Mozart met G. B. Martini in Bologna, and was accepted as a member of the famous Accademia Filarmonica. In Rome he heard Gregorio Allegri’s Miserere once in performance in the Sistine Chapel. He wrote it out in its entirety from memory, only returning to correct minor errors – thus producing the first illegal copy of this closely guarded property of the Vatican.

In Milan, Mozart wrote the opera Mitridate, re di Ponto (1770), which was performed with success. This led to further opera commissions. He returned with his father later twice to Milan (August – December 1771; October 1772 – March 1773) for the composition and premieres of Ascanio in Alba (1771) and Lucio Silla (1772). The father hoped these visits would result in a professional appointment for his son in Italy but such hopes were never fulfilled.

Toward the end of the final Italian journey Mozart wrote the first of his works to be still widely performed today, the solo cantata Exsultate, jubilate, K. 165.

Salzburg and Vienna (1772 – 1781)

The Salzburg court

After finally returning with his father from Italy on 13rd of March 1773, Mozart was employed as a court musician by the ruler of Salzburg, Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo. The composer had a great number of friends and admirers in Salzburg and had the opportunity to work in many genres, composing symphonies, sonatas, string quartets, serenades, and a few minor operas. Several of these early works are still performed today. Between April and December 1775, Mozart developed an enthusiasm for violin concertos, producing a series of five (the only ones he ever wrote), which steadily increased in their musical sophistication. The last three – K. 216, K. 218, K. 219 – are now staples of the repertoire. In 1776 he turned his efforts to piano concertos, culminating in the E-flat concerto K. 271 of early 1777, considered by critics to be a breakthrough work.

Despite these artistic successes, Mozart grew increasingly discontented with Salzburg and redoubled his efforts to find a position elsewhere. One reason was his low salary, 150 florins a year; Mozart also longed to compose operas and Salzburg provided only rare occasions for these. The situation worsened in 1775 when the court theater was closed, especially since the other theater in Salzburg was largely reserved for visiting troupes.

Two long expeditions in search of work (both Leopold and Wolfgang were looking) interrupted this long Salzburg stay: they visited Vienna, from 14th of July to 26th of September 1773, and Munich, from 6th of December 1774 to March 1775. Neither visit was successful, though the Munich journey resulted in a popular success with the premiere of Mozart’s opera La finta giardiniera.

The Paris journey

Family portrait from about 1780 by Johann Nepomuk della Croce: Nannerl, Wolfgang, Leopold. On the wall is a portrait of Mozart’s mother, who had died in 1778.

In August 1777 Mozart resigned his Salzburg position and, on 23 September, ventured out once more in search of employment, with visits to Augsburg, Mannheim, Paris, and Munich. Since Archbishop Colloredo would not give Leopold leave to travel, Mozart’s mother Anna Maria accompanied him.

Mozart became acquainted with members of the famous orchestra in Mannheim, the best in Europe at the time. He also fell in love with Aloysia Weber, one of four daughters in a musical family. There were prospects of employment in Mannheim, but they came to nothing, and Mozart left for Paris on 14th of March 1778 to continue his search. One of his letters from Paris hints at a possible post as an organist at Versailles but Mozart was not interested in such an appointment. He fell into debt and took to pawning valuables. The nadir of the visit occurred when Mozart’s mother took ill and died on 3rd of July 1778. There had been delays in calling a doctor – probably, according to Halliwell, because of a lack of funds.

While Wolfgang was in Paris, Leopold was pursuing opportunities for him back in Salzburg and, with the support of local nobility, secured him a post as court organist and concertmaster. The yearly salary was 450 florins but Wolfgang was reluctant to accept. After leaving Paris on 26th of September 1778, he tarried in Mannheim and Munich, still hoping to obtain an appointment outside Salzburg. In Munich he again encountered Aloysia, now a very successful singer, but she made it plain that she was no longer interested in him. Mozart finally reached home on 15th of January 1779 and took up the new position but his discontent with Salzburg was undiminished.

Departure to Vienna

In January 1781 Mozart’s opera Idomeneo premiered with “considerable success” in Munich. The following March the composer was summoned to Vienna, where his employer, Archbishop Colloredo, was attending the celebrations for the accession of Joseph II to the Austrian throne. Mozart, fresh from the adulation he had earned in Munich, was offended when Colloredo treated him as a mere servant and particularly when the archbishop forbade him to perform before the Emperor at Countess Thun’s for a fee equal to half of his yearly Salzburg salary. The resulting quarrel came to a head in May: Mozart attempted to resign and was refused. The following month, permission was granted but in a grossly insulting way: the composer was dismissed literally “with a kick in the ass”, administered by the archbishop’s steward, Count Arco. Mozart decided to settle in Vienna as a freelance performer and composer.

The quarrel with the archbishop went harder for Mozart because his father sided against him. Hoping fervently that he would obediently follow Colloredo back to Salzburg, Leopold exchanged intense letters with his son, urging him to be reconciled with their employer. Wolfgang passionately defended his intention to pursue an independent career in Vienna. The debate ended when Mozart was dismissed by the archbishop, freeing himself both of his employer and his father’s demands to return. Solomon characterizes Mozart’s resignation as a “revolutionary step”, and it greatly altered the course of his life.

At Vienna (1782 – 1790)

Early Vienna years

Mozart’s new career in Vienna began well. He performed often as a pianist, notably in a competition before the Emperor with Muzio Clementi on 24th of December 1781, and he soon “had established himself as the finest keyboard player in Vienna”. He also prospered as a composer, and in 1782 completed the opera “Die Entführung aus dem Serail” (“The Abduction from the Seraglio”), which premiered on 16th of July 1782 and achieved a huge success. The work was soon being performed “throughout German-speaking Europe”, and fully established Mozart’s reputation as a composer.

Near the height of his quarrels with Colloredo, Mozart moved in with the Weber family, who had moved to Vienna from Mannheim. The father, Fridolin, had died, and the Webers were now taking in lodgers to make ends meet. Aloysia, who had earlier rejected Mozart’s suit, was now married to the actor Joseph Lange, and Mozart’s interest shifted to the third daughter, Constanze. The courtship did not go entirely smoothly; surviving correspondence indicates that Mozart and Constanze briefly broke up in April 1782. Mozart also faced a very difficult task in getting his father’s permission for the marriage. The couple were finally married on 4th of August 1782, in St. Stephen’s Cathedral, the day before Leopold’s consent arrived in the mail.

In the course of 1782 and 1783 Mozart became intimately acquainted with the work of Johann Sebastian Bach and George Friederich Handel as a result of the influence of Gottfried van Swieten, who owned many manuscripts of the Baroque masters. Mozart’s study of these scores inspired compositions in Baroque style, and later influenced his personal musical language, for example in fugal passages in “Die Zauberflöte” (“The Magic Flute”) and the finale of Symphony No. 41.

In 1783 Wolfgang and Constanze visited his family in Salzburg. Leopold and Nannerl were, at best, only polite to Constanze, but the visit prompted the composition of one of Mozart’s great liturgical pieces, the Mass in C minor. Though not completed, it was premiered in Salzburg, with Constanze singing a solo part.

Mozart met Joseph Haydn in Vienna, and the two composers became friends (see Haydn and Mozart). When Haydn visited Vienna, they sometimes played together in an impromptu string quartet. Mozart’s six quartets dedicated to Haydn (K. 387, K. 421, K. 428, K. 458, K. 464, and K. 465) date from the period 1782 to 1785, and are judged to be a response to Haydn’s Opus 33 set from 1781. Haydn in 1785 told the visiting Leopold: “I tell you before God, and as an honest man, your son is the greatest composer known to me by person and repute, he has taste and what is more the greatest skill in composition.”

From 1782 to 1785 Mozart mounted concerts with himself as soloist, presenting three or four new piano concertos in each season. Since space in the theaters was scarce, he booked unconventional venues: a large room in the Trattnerhof (an apartment building), and the ballroom of the Mehlgrube (a restaurant). The concerts were very popular, and the concertos he premiered at them are still firm fixtures in the repertoire. Solomon writes that during this period Mozart created “a harmonious connection between an eager composer-performer and a delighted audience, which was given the opportunity of witnessing the transformation and perfection of a major musical genre”.

With substantial returns from his concerts and elsewhere, he and Constanze adopted a rather plush lifestyle. They moved to an expensive apartment, with a yearly rent of 460 florins. Mozart also bought a fine fortepiano from Anton Walter for about 900 florins, and a billiard table for about 300 florins. The Mozarts sent their son Karl Thomas to an expensive boarding school, and kept servants. Saving was therefore impossible, and the short period of financial success did nothing to soften the hardship the Mozarts were later to experience.

On 14th of December 1784 Mozart became a Freemason, admitted to the lodge “Zur Wohltätigkeit” (“Beneficence”). Freemasonry played an important role in the remainder of Mozart’s life: he attended meetings, a number of his friends were Masons, and on various occasions he composed Masonic music. (See Mozart and Freemasonry.)

Return to opera

Despite the great success of “Die Entführung aus dem Serail” Mozart did little operatic writing for the next four years, producing only two unfinished works and the one-act “Der Schauspieldirektor”. He focused instead on his career as a piano soloist and writer of concertos. However, around the end of 1785, Mozart moved away from keyboard writing and began his famous operatic collaboration with the librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte. 1786 saw the successful premiere of “The Marriage of Figaro” in Vienna. Its reception in Prague later in the year was even warmer, and this led to a second collaboration with Da Ponte: the opera “Don Giovanni”, which premiered in October 1787 to acclaim in Prague, and also met with success in Vienna in 1788. The two are among Mozart’s most important works and are mainstays of the operatic repertoire today, though at their premieres their musical complexity caused difficulty for both listeners and performers. These developments were not witnessed by the composer’s father, as Leopold had died on 28th of May 1787.

In December 1787 Mozart finally obtained a steady post under aristocratic patronage. Emperor Joseph II appointed him as his “chamber composer”, a post that had fallen vacant the previous month on the death of Gluck. It was a part-time appointment, paying just 800 florins per year, and only required Mozart to compose dances for the annual balls in the Redoutensaal. However, even this modest income became important to Mozart when hard times arrived. Court records show that Joseph’s aim was to keep the esteemed composer from leaving Vienna in pursuit of better prospects.

In 1787 the young Ludwig van Beethoven spent several weeks in Vienna, hoping to study with Mozart. No reliable records survive to indicate whether the two composers ever met. (See Mozart and Beethoven.)

Toward the end of the decade Mozart’s circumstances worsened. Around 1786 he had ceased to appear frequently in public concerts, and his income shrank. This was a difficult time for musicians in Vienna because Austria was at war, and both the general level of prosperity and the ability of the aristocracy to support music had declined.

By mid-1788 Mozart and his family had moved from central Vienna to the suburb of Alsergrund. Although it has been thought that Mozart reduced his rental expenses, recent research shows that by moving to the suburb Mozart had certainly not reduced his expenses (as claimed in his letter to Puchberg), but merely increased the housing space at his disposal. Mozart began to borrow money, most often from his friend and fellow Mason Michael Puchberg; “a pitiful sequence of letters pleading for loans” survives.Maynard Solomon and others have suggested that Mozart was suffering from depression and it seems that his output slowed. Major works of the period include the last three symphonies (No. 39, 40, and 41, all from 1788), and the last of the three Da Ponte operas, “Così fan tutte”, premiered in 1790.

Around this time Mozart made long journeys hoping to improve his fortunes: to Leipzig, Dresden, and Berlin in the spring of 1789 and to Frankfurt, Mannheim, and other German cities in 1790. The trips produced only isolated success and did not relieve the family’s financial distress.

Last works and early death (1791)

Mozart’s last year was, until his final illness struck, a time of great productivity and by some accounts a time of personal recovery. He composed a great deal, including some of his most admired works: the opera “The Magic Flute”, the final piano concerto (K. 595 in B-flat), the Clarinet Concerto K. 622, the last in his great series of string quintets (K. 614 in E-flat), the motet Ave verum corpus K. 618, and the unfinished Requiem K. 626. Mozart’s financial situation, a source of extreme anxiety in 1790, finally began to improve.

Although the evidence is inconclusive, it appears that wealthy patrons in Hungary and Amsterdam pledged annuities to Mozart in return for the occasional composition. He probably also benefited from the sale of dance music written in his role as Imperial chamber composer. Mozart no longer borrowed large sums from Puchberg, and made a start on paying off his debts.He experienced great satisfaction in the public success of some of his works, notably “The Magic Flute” (performed many times in the short period between its premiere and Mozart’s death) and the Little Masonic Cantata K. 623, premiered on 15th of November 1791.

Death of Mozart

Mozart fell ill while in Prague for the premiere on 6th of September of his opera “La clemenza di Tito”, written in 1791 on commission for the Emperor’s coronation festivities. He was able to continue his professional functions for some time, and conducted the premiere of “The Magic Flute” on 30th of September. The illness intensified on 20th of November, at which point Mozart became bedridden, suffering from swelling, pain, and vomiting.

Mozart was nursed in his final illness by Constanze and her youngest sister Sophie, and attended by the family doctor, Thomas Franz Closset. It is clear that he was mentally occupied with the task of finishing his Requiem. However, the evidence that he actually dictated passages to his student Süssmayr is very slim.

Mozart died at 1 am on 5th of December 1791 at the age of 35. The New Grove gives a matter-of-fact description of his funeral:

Mozart was buried in a common grave, in accordance with contemporary Viennese custom, at the St. Marx Cemetery outside the city on 7th of December. If, as later reports say, no mourners attended, that too is consistent with Viennese burial customs at the time; later Jahn (1856) wrote that Salieri, Süssmayr, van Swieten and two other musicians were present. The tale of a storm and snow is false; the day was calm and mild.

The cause of Mozart’s death cannot be known with certainty. The official record has it as “hitziges Frieselfieber” (“severe miliary fever”, referring to a rash that looks like millet seeds), a description that does not suffice to identify the cause as it would be diagnosed in modern medicine. Researchers have posited at least 118 causes of death, including trichinosis, influenza, mercury poisoning, and a rare kidney ailment. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that Mozart died of acute rheumatic fever.

Mozart’s sparse funeral did not reflect his standing with the public as a composer: memorial services and concerts in Vienna and Prague were well attended. Indeed, in the period immediately after his death, Mozart’s reputation rose substantially: Solomon describes an “unprecedented wave of enthusiasm”, for his work; biographies were written (first by Schlichtegroll, Niemetschek, and Nissen; see Biographies of Mozart); and publishers vied to produce complete editions of his works.

© Wikipedia, 2010